There is a scale to Denis Villeneuve's Dune that borders on the biblical. Monolithic spaceships hang like moons in the heavens. Worms the size of skyscrapers swim like sharks through the desert. Extreme wide shots frame the barren planet of Arrakis as a vast unknowable ocean of sand, its dunes fluttering in the wind like waves. And yet it is not only size that makes Dune one of the most striking science-fiction films of recent years. It is how it marries that grandeur with slow, atmospheric and considered filmmaking – where shots live long, and scenes breathe freely.

More like this:

- The erotic thriller that still shocks

- 'The spy story to end all spy stories'

- Is it time to revive the epic romance?

Such a balance between blockbuster scale and arthouse sensibility has come to typify the work of Denis Villeneuve, the French-Canadian director who, in the space of a decade, has risen to become one of the 21st Century's biggest, most challenging science-fiction filmmakers. Just take 2016's Arrival, a melancholy love story set around an alien language that allows the user to see through time; or Blade Runner 2049, the 2017 sequel whose moody exploration of what it means to be human thrilled critics but performed disappointedly at the box office. And now there's Dune, the long-awaited adaptation of Frank Herbert's sprawling 1960s magnum opus.

He would probably be described as an auteur. He has a clear vision of what he wants to do – Helen O'Hara

"It was a big leap up to Arrival. It was a very big leap up to Blade Runner 2049. It's been a leap even from there to Dune," says film journalist Helen O'Hara, who visited the set of Dune for Empire magazine. "And I think that's because he's had pretty unfailingly good reviews throughout his career. Even when they haven't been massive box-office successes, he's been heralded for his undoubted talent and his very good eye… He would probably be described as an auteur. He has a clear vision of what he wants to do. He's very attracted to big ideas in his movies, and that's true of his smaller-scale dramas as well as his science fiction. Arrival is a 'big ideas' movie. Blade Runner 2049 was a 'big ideas' take on Blade Runner, which is itself a big ideas movie, and Dune is dealing with huge civilisation-wide questions."

Villeneuve himself once described his career as a series of karate belts, with each film representing a step up in size and difficulty. With Dune, it's hard not to think that he is only one or two punches away from becoming a master.

Denis Villeneuve with actor Timothée Chalamet on the set of Dune (Credit: Legendary Pictures)

When Denis Villeneuve first started to take meetings in Hollywood, he would tell any executive who would listen that he wanted to make a science-fiction movie. He had been a fan of the genre since he was a child, when he fell in love with films such as Blade Runner and 2001: A Space Odyssey. But, as a young independent filmmaker, he didn't have the means to fund the necessary special effects. As he once said himself, in response to a question on why he had suddenly turned away from grounded mid-budget dramas in favour of science fiction: "I didn't turn to science fiction, I went away from it."

Career shift

Villeneuve's early films give a poor impression of the director he was to become. His 1998 debut, August 32nd on Earth, is a haphazard romcom full of frantic camera movement and jump cuts; while his follow-up, 2000's Maelstrom, is a surreal psychological drama narrated by a talking fish. He has since dismissed these efforts as arrogant and self-indulgent. Hence why he wouldn't make another film for nine years, focusing instead on helping to raise his children and better his craft.

He decided during that period that if he ever returned to directing it would be to make a film for others rather than himself. This led to 2009's Polytechnique, a stark black-and-white drama inspired by a misogynistic shooting at a Montreal university; before moving on to 2010's Incendies, a harrowing story about two Canadian siblings who travel to the Middle East to find their long-lost father and brother. Sober, measured, elegant – they were to be his calling card for Hollywood.

I find Denis very thoughtful. He's not somebody who just directs from a script. He's always searching for something more than what's on a page – Roger Deakins

"I really wanted to work with him when I saw Incendies," says cinematographer Roger Deakins, one of Villeneuve's most frequent and renowned collaborators. "I said to my agent, 'if he ever makes a film in America, put my name in the hat'. And I was very lucky that Denis responded when he was about to do Prisoners."

The thematically bleak Prisoners, a 2013 drama starring Hugh Jackman as the violent father of a kidnapped child, represented something of a refinement of Villeneuve's directorial voice. His camera became even more restrained, content to linger upon the window of a shot for as long as possible before the cut. And even when the camera did move, it moved slowly, creeping like a killer. It's an austere style that worked well with Deakins' cinematography, famed for shrouding characters in blankets of shadow. They would work together again on 2015 cartel thriller Sicario, and in 2017 on Blade Runner 2049.

Denis Villeneuve and Director of Photography Roger Deakins on the set of thriller Prisoners; they have worked together on three films (Credit: Warner Bros Pictures)

"I find Denis very thoughtful," says Deakins. "He's not somebody who just directs from a script. He's always searching for something more than what's on a page. His style of filmmaking is pretty exceptional these days. It probably owes more to Eastern-European or Japanese filmmaking than it does to American filmmaking." Deakins adds that he admires the fact that Villeneuve does not shoot a lot of coverage, referring to the process of surrounding a scene with multiple cameras. "He says 'this is the shot', and basically that is what you shoot," he explains. "I like spending time in prep. I like breaking a script down to its essence and a scene down into specific shots. I don't like going on to a set and just shooting every possible option. I like considered filmmaking. And Denis is that."

One of the best science-fiction films ever made is Solaris. It's a much more thoughtful film than 2001, because it's about character – Roger Deakins

The actor David Dastmalchian, who has appeared in Prisoners, Blade Runner 2049 and Dune, once told The Hollywood Reporter that Denis Villeneuve "is a genius… he's our generation's Stanley Kubrick". A tad hyperbolic, perhaps, but you can see where he's coming from. Villeneuve himself cites 2001: A Space Odyssey as a major influence on his work. But Roger Deakins sees more in common with Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky, who used science fiction as a means to tell intimate, psychologically complex stories. "One of the best science-fiction films ever made is [1972's] Solaris," he says, "It's a much more thoughtful film than 2001, because it's about character. It's not about amazing special effects." The truth is probably somewhere between the two.

"He approaches everything, first and foremost, from a place of character and theme," explains Legendary Pictures' Mary Parent, a producer on Dune. "And in science fiction, there are certainly filmmakers who approach it with an emphasis on fantastical worlds, which are incredible, but that can sometimes overwhelm everything else. But also, the authenticity of his worldbuilding is jaw-dropping. It's part of what makes his character stories so rich. It all feels incredibly real."

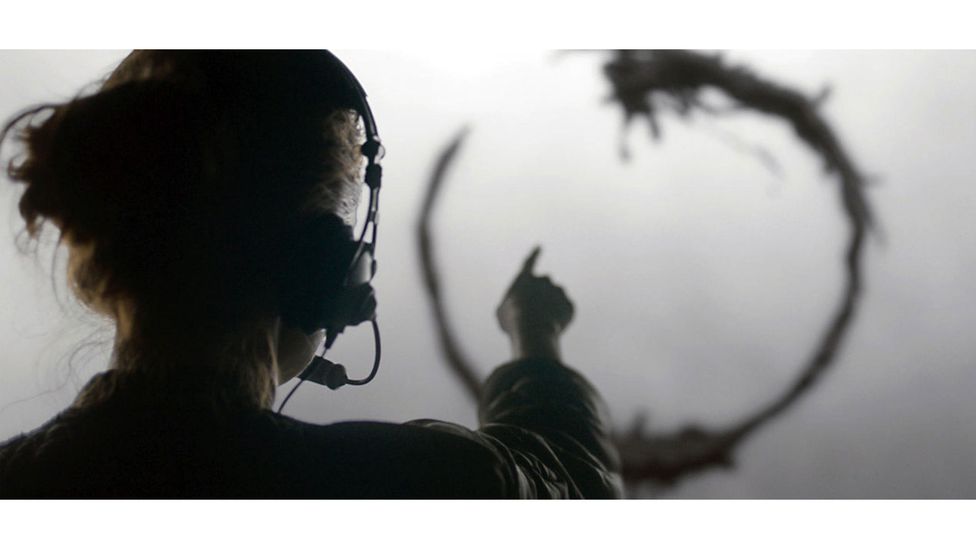

In Arrival, decoding an alien language gives a character a different view of time (Credit: 21 Laps Entertainment)

There is perhaps no better example of this approach than 2016's Arrival, the film that finally fulfilled Villeneuve's long-standing ambition to make science fiction. Written by screenwriter Eric Heisserer, who adapted it from a short story called Story of Your Life by Ted Chiang, it tells the tale of Louise, a linguist played by Amy Adams, who is recruited to make first contact with a race of aliens who have caused chaos by landing in 12 different locations on Earth. Like a lot of Villeneuve's science fiction, it grounds its more outlandish elements in sober realism (a sequence where people crowd around televisions to watch the news brings to mind 9/11), but is unashamedly lyrical and sentimental too.

Circles are a recurring theme in Villeneuve's work. You can see it in Incendies, with a family that is caught in an inter-generation cycle of misery and trauma. You can see it in the cruel worlds of Sicario and Prisoners, where violence only breeds more violence. But in Arrival, you can see the circles writhing in the air – a product of the aliens' unique written language, which takes the form of complete thoughts expressed instantly, with no beginning or end. Learning the language herself allows Louise to experience time as the aliens do: as a circle, with no distinction between present or future, beginning or end. This leads to her being haunted by visions of the dying child she is yet to have, of a cycle of time she is helpless to break. But even if you know it's coming, isn't the pain and grief worth the joy? Is it better to have loved and lost than to have never loved at all?

"I think people are quick to see coldness in science fiction," says O'Hara, "and I don't think that's always fair. Arrival is very uncold, I think there's a lot of emotion bubbling under the surface. The fact that Amy Adams wasn't nominated for an Oscar is insane to me." O'Hara goes on to draw comparisons with another contemporary director famed for his big budget science fiction. "I think he has a little bit more heart than Christopher Nolan. The fans might disagree with me on that, but I feel like Villeneuve has a bit more emotion in his films. I think he has much better female roles as well."

And yet, unlike the more populist offerings of Nolan, perhaps Villeneuve's brand of slow and cerebral science fiction has its limits.

After making waves with the critical and commercial success of Arrival, Villeneuve embarked on the greatest challenge of his career: making a sequel to Ridley Scott's 1982 science-fiction classic Blade Runner. Villeneuve was daunted by the task. In a recent interview he talks about "flirting with disaster", and about fears that he may never work again. This was, he says, a potential act of sacrilege.

While Blade Runner 2049 was underwhelming at the box office, it was a critical success (Credit: Warner Bros Pictures)

Set 30 years after the original film, Blade Runner 2049 follows the story of Ryan Gosling's K, a dead-eyed replicant who helps the Los Angeles Police Department to hunt down and "retire" (kill) other replicants. It is a job that becomes complicated when he discovers evidence of a replicant who has given birth. "I've never retired something that was born before," K tells his boss at one point. She asks him what the difference is. "To be born is to have a soul, I guess."

It is, without a doubt, Villeneuve's most visually arresting film, with the director and Deakins using a range of rich colour schemes, textured lighting design and opulent science-fiction imagery to create a future you could not only taste and smell, but dread. "Denis wanted to set everything in a reality that was stretched," says Deakins, referring to the film's climate-change overtones. "So when we saw things like the red-dust storm that hit Sydney [in 2009], that became a template for Las Vegas. That's great science fiction: projecting into the future where science will go."

But Blade Runner 2049 is also one of Villeneuve's most difficult films. Clocking in at two hours and 43 minutes, it's a long and pensive noir, thick with themes of authenticity and alienation. What does it mean to be alive? It's a question asked by Blade Runner before, but this time comes with a subversive twist, as K finds out that he is not, as previously thought, the chosen one. But does being a nobody mean that his life is suddenly devoid of purpose? Or is meaning something that you make yourself? Such weighty questions make Blade Runner 2049 one of Villeneuve's best, most interesting films, but also one that returned $259 million on an estimated $300 million marketing-and-production budget.

"It is thoughtful," says Deakins. "And I don't know if people want thoughtful films. I think that's the way the world is. I don't think it is just films. People aren't interested in looking deeper into things, they want instant gratification and instant solutions."

Simply put, is there a market big enough for science fiction this slow, cerebral and sombre, made on this sort of scale?

Box office isn't everything in Hollywood. Sometimes, failing a total disaster, the awards and prestige of working with a visionary director is enough. But Blade Runner 2049's box-office performance does raise intriguing questions for Dune. The original book is notorious for its long and expansive story, layered with dense mythology, political machinations and a main character (Paul, played by Timothée Chalamet) who is plagued by visions of various possible futures. The first book is so long and expansive, in fact, that Villeneuve is hoping to tell it over the course of two parts (lest he repeats the errors of David Lynch's jarringly cramped 1984 version). But simply put, is there a market big enough for science fiction this slow, cerebral and sombre, made on this sort of scale?

"I really loved Blade Runner 2049," says Parent. "I thought that it was an incredible film, but [Dune and Blade Runner 2049] are different offerings. They may be in the same genre, but the story of Dune is much more accessible and relatable. Blade Runner 2049, just by nature, storyline and being a noir, was a smaller film. Dune is more of an adventure story." How does she feel about their chances of making part two? "We've opened the film on a limited basis internationally, we've yet to open in some of the bigger territories, but so far so good," she says. "'Cautiously optimistic' is probably the best way to put it. I don't want to jinx anything… To Denis's credit, he's really balanced something that has all those [cerebral] elements but at the same time is very thrilling".

Villeneuve is planning to make a second part of Dune, hoping to avoid the pitfalls that earlier directors like David Lynch fell into (Credit: Legendary Pictures)

"I think that we underestimate audiences at our peril," says Helen O'Hara. "I think that something like Dune has sold in book form for decades, and there's a reason for that. They're probably right to throw the dice and see how well a faithful film version does… Why did we get the idea that there has to be loads of gags in a sci-fi movie, you know? It can't all just be Guardians of the Galaxy, there has to be room for other stories as well. I do genuinely think there's an audience for this. It might not be Avengers Endgame-sized audiences, but it is a big enough audience, potentially, long-term, to keep this movie going."

And even if Dune doesn't succeed, adds O'Hara, the fact that filmmakers like Denis Villeneuve exist, and that they're still being given the chances to make big risky movies within the major studio system, is at least something to be grateful for.

"It gives me hope," she says. "The fact that a studio invested this much money in him, and his next film after Blade Runner was not a huge hit – I think that is a really good thing. That's what we want to see. We want to see good directors get multiple chances, especially if they make a good film that just doesn't do well at the box office. We want to see them get a follow-up film. I think it says good things that he's getting to make this, and I really, really hope it does well enough that he gets to make part two."

After all, it is not like Denis Villeneuve to leave a circle incomplete.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Post a Comment