Belarus has been accused of taking revenge for EU sanctions by offering migrants tourist visas, and helping them across its border. The BBC has tracked one group trying to reach Germany.

The mobile phone camera pans left and right, but no-one moves. The exhausted travellers lie scattered among the trees.

Jamil has his head in his hands, his wife Roshin slumped forward next to him. The others look dead.

Late afternoon light slants through the forest, the pine trees forming a dense natural prison. They've been walking since four in the morning.

"We're shattered, absolutely shattered," Jamil's cousin Idris intones, almost mechanically.

The Syrian friends have fought through thickets and waded through foul-smelling swamps to get here. They've already missed their first rendezvous with a smuggler, and they've run out of food and water.

The Syrians are numb with cold but don't dare light a fire. They've crossed from Belarus into Poland, so have finally made it to the EU. But they're not safe yet. Thousands of others, encouraged by Belarus to cross into Poland, Lithuania and Latvia, have ended up in detention instead. At least seven have died of hypothermia in the Polish forest.

We've been tracking Idris and his friends since they left northern Iraq in late September. Idris has recorded their progress on his phone and sent us a series of videos along the way.

The group are Syrian Kurds, in their 20s, looking to Europe for a better future. They are all from Kobane, the scene of ferocious fighting between Kurdish fighters and Islamic State militants in late 2014.

But while their motives - political instability at home, fear of conscription, lack of employment - are the familiar refrain of migrants the world over, the route they have taken is new.

Idris admits he might not have tried to leave Syria if Belarus's autocratic leader, Alexander Lukashenko, had not offered a new, apparently safer route.

"Belarus has an ongoing feud with the EU," he told me, when I asked him why he had decided to attempt the journey to Europe. "The Belarus president decided to open its borders with the EU."

Idris was referring to Mr Lukashenko's warning earlier this year, that he would no longer stop migrants and drugs from crossing into EU member states.

The Belarus president had been infuriated by successive waves of EU sanctions, imposed following his country's disputed 2020 presidential election, the subsequent hounding of political opponents, and the forced diversion of a RyanAir jet carrying an opposition journalist and his girlfriend.

Officials in neighbouring Lithuania say they saw warning signs as early as March.

"It started as indications from the Belarusian government that they are ready to simplify visa proceedings… for 'tourists' from Iraq," Lithuania's Deputy Minister of Interior, Kestutis Lancinskas tells us.

Instead of taking hazardous journeys by boat across the Mediterranean, all migrants now need to do is fly to Belarus, drive for several hours to the border, and then simply cross on foot into one of the three neighbouring EU countries - Poland, Lithuania and Latvia.

In July and August, Lithuania saw 50 times more asylum seekers than in the whole of 2020.

"The route is obviously a lot easier than going through Turkey and North Africa," Idris said.

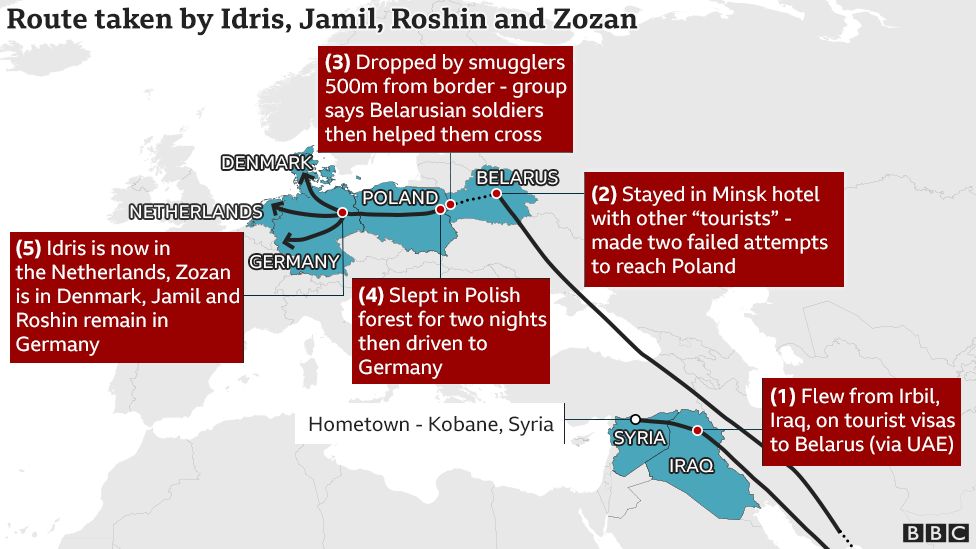

He and his friends had started out from Irbil in northern Iraq on 25 September. Idris had been working there and left his wife and twin baby daughters in Kobane, promising they could eventually join him in Europe if he made it.

They are part of a generation of Syrians whose lives have been blighted by 10 years of civil war. Idris has already spent time as a refugee in neighbouring Turkey.

"It's a long story, my friend, and I regret many things," Idris told me over the phone when I asked him what motivated him.

"But nothing's in our control. There's no future for me in Syria."

In one of Idris's first videos, recorded outside Irbil airport, he is clearly upbeat about the journey ahead. They've got their tickets, and seven-day tourist visas for Belarus. They're ready to go.

The process so far had been relatively simple. To find out just how simple, we flew to northern Iraq to meet the people involved.

Irbil is the bustling capital of the country's autonomous Kurdish region. A city of more than one-and-a-half million people, it's home to hundreds of thousands of refugees from neighbouring Syria, as well as other parts of Iraq.

For many, it's also where the journey to Europe begins.

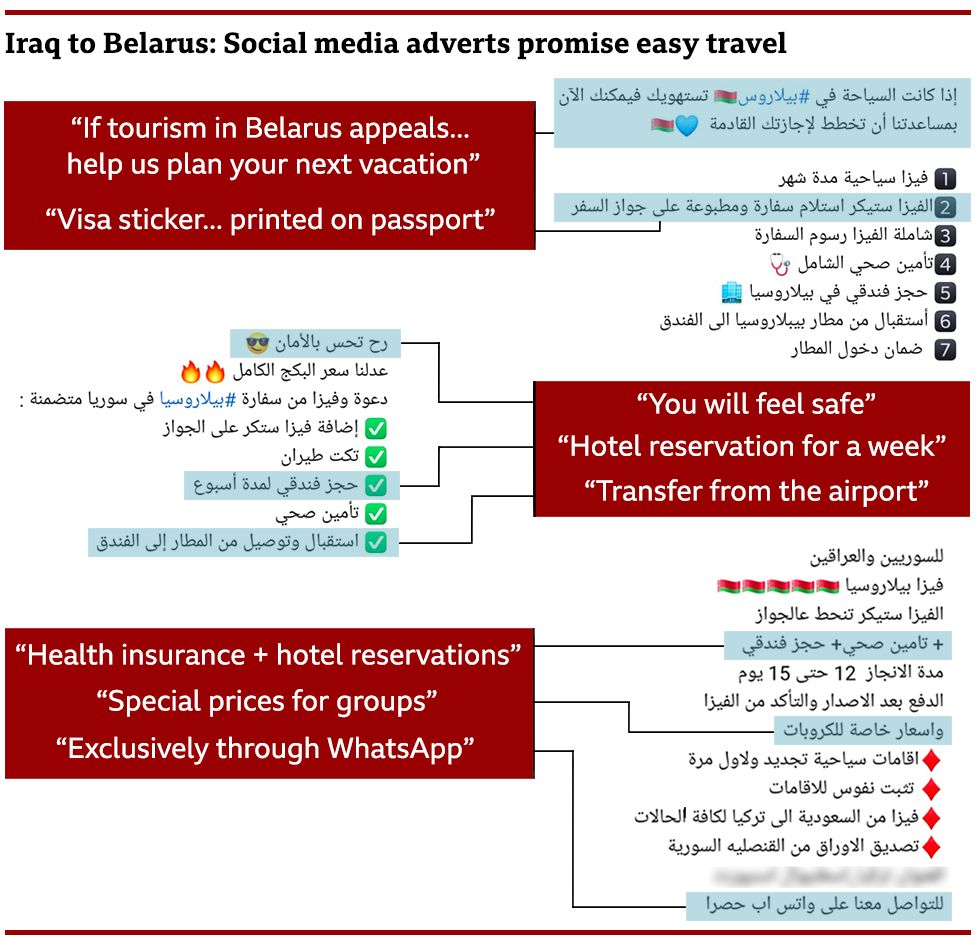

Not that you'd know that immediately. There are travel agents, to be sure. Lots of them. But this is a word of mouth business, with travel tips disseminated online in Facebook and chat groups.

In an office strewn with passports - mostly Syrian - Murad took me through the process. Murad is not his real name. Even though his role is not illegal - all he does is arrange the visas and flights to the Belarusian capital Minsk - he doesn't want to be identified.

Back in the summer, with news of Mr Lukashenko's threat to the EU bouncing all over social media, Murad contacted friends in Belarus, asking about the new visa rules.

"They said 'yes, it's easy now'," Murad recalled.

"I knew it's going to be the same as what happened in 2015 with Turkey."

In 2015, Turkey's President, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, was also in dispute with the EU. He allowed hundreds of thousands of migrants to pass through his country, until the EU agreed to a €6bn (£5bn) deal to help Ankara meet the cost of the influx.

For migrants now looking for safe passage via Minsk, Belarusian travel companies initially issued electronic invitations to allow people to board flights for the capital.

But as cowboy operations started to make money from fake invitations, the rules changed. Now, migrants need a physical visa stamp in their passport before they can book a flight. It takes longer, but still isn't complicated.

Next, a smuggler. This is where it gets expensive.

Murad said he didn't work with smugglers, advising his clients that it's actually cheaper and more reliable to find one when they reach Minsk. But when we met one ourselves, it was on the street outside Murad's office and the two men clearly knew each other.

We were told that Jouwan - again not his real name - was a veteran smuggler, having arranged trips through Turkey and Greece during the 2015 migration crisis.

"If you're using a smuggler," said Jouwan, "it's going to cost you a lot. Between $9,000 and $12,000."

After all, it was an unpredictable journey, Jouwan said.

"You're going through unknown woods, in a foreign country. Robbers are waiting to snatch your money. The mafia is watching you. There are wild animals on the loose, rivers and swamps to cross. You're leaping into the unknown, even if you're using GPS."

Asked about the authorities in Belarus, Jouwan was clear about their role.

"They're facilitating the issue. They're helping people."

When Idris and his friends reached the Belarusian capital Minsk, they found it teeming with migrants all beating the same path to Europe. Idris's footage from Minsk airport shows a crammed arrivals hall - passengers sprawled out across the floor waiting to be processed.

Like many who pass this way, Idris and his friends had reservations at Minsk's Sputnik Hotel, which advertises itself as "ideal for business trips and family holidays".

Others have been less fortunate. Footage shared on social media claims to show migrants in sleeping bags, sheltering in a nearby underpass.

When I reached Idris by phone, he told me they were in touch with smugglers to take them across the Polish border and on to Germany. Their departure was imminent. Idris acknowledged the challenges ahead.

"We're crossing the borders illegally. We don't know what will happen. We can't trust anyone, not even our smuggler. We're putting our fate in God's hands."

The trip from Irbil to Belarus, he said, had already cost $5,000 (£3,600) per person, including airfare, hotel reservations and tourist visas. They were still haggling with smugglers about the onward journey.

A day later, we spoke again. There had been a setback. The group had left Minsk too late to meet a smuggler and make it into Poland. They were now at another hotel, close to the border. The costs were piling up. The group had to take two private cars from Minsk, paying $400 for each.

Trepidation was setting in, because for all the expense, the outcome could still be disastrous.

"We don't know whether we're going to make it or not," he told me. "Are we going to get stuck in the woods, or will it just be a matter of four or five hours [walking], just like the smuggler told us?"

Another short video arrived before they set off.

"Pray for us," Idris says into the camera.

Across Belarus's north-western border, in Lithuania, we found that the prayers and dreams of thousands of migrants like Idris had been shattered. By August, more than 4,000 had made it across a largely unfenced border.

Some made the onward journey to Western Europe, but many were caught. They're now being held in detention centres across the country while Lithuania figures out what to do with them. While some have been granted asylum, so far this has not included any Syrians or Iraqis.

At Kybartai, in the west, more than 670 migrants have been moved to a converted prison. The authorities are trying to make it as habitable as possible. The warm cells are a definite improvement on the tented camps near the border where the migrants were being accommodated until recently.

But when we visited, the high walls, razor wire and watchtowers created an unmistakably grim atmosphere. "I need freedom," several people shouted from their cells.

The inmates were all single men, from more than 20 different countries. Most were Iraqis and Syrians, but others had come from as far afield as Yemen, Sierra Leone and even Sri Lanka.

Abbas, from Iraq, said conditions were terrible and the migrants were being treated like criminals.

"Is it our fault Belarus opened its borders to the EU?" he asked.

At the end of his journey he was briefly detained by the Belarusian border guards. But it seemed all they had wanted was a souvenir.

"They took selfies with us and showed us the way," he said.

Fed up with his treatment and aware that his $11,000 journey had come to an abrupt, humiliating end, Abbas said he was thinking of going back.

"But I'm not going to live in Iraq. I'll live in Turkey. I have no idea what's going to happen though. I don't have any money."

But even though the detainees recognised they were pawns in a geopolitical tussle between Belarus and the EU, they mostly thanked Mr Lukashenko for giving them this chance.

"When I get out, I'm going to get his name tattooed on my arm," Azzal, another Iraqi, told me.

The flow of migrants into Lithuania has now been stemmed, thanks in part to the country's increased border security, assisted by the EU's border management agency, Frontex. But guards also showed us places where the border was still poorly protected, sometimes little more than a gap in the forest.

At one such spot, Belarusian border guards and soldiers sauntered past on the other side, filming us on a mobile phone but avoiding eye contact.

"In old times we had really good communication about illegal immigrants," Vytautas Kuodis, of Lithuania's State Border Guard Service, told me.

All that ended over the summer. Calls from the Lithuanian side now go unanswered.

"Mostly they ignore us," Mr Kuodis said.

Although dozens of migrants still try to cross into Lithuania each day from Belarus, most are now heading for Poland.

Idris and his friends' second attempt to cross the Polish border ended - like their first - in failure.

Videos, shot furtively on Idris's mobile phone, show tense roadside conversations, with voices in Russian, English and Arabic. There was a scary encounter with Belarusian police, who stopped the group, took their passports and told the drivers to return the migrants to Minsk.

They drove back to the Sputnik Hotel, where the drivers then demanded a fee to recover the group's passports from the police. At the hotel, Idris and his friends now discovered a growing network of smugglers, sorting out accommodation and logistics. And the hotel was full of new arrivals - Syrians, Iraqis and Yemenis.

"The numbers are increasing every day," Idris says in a video shot outside the Sputnik.

To add to the group's complications, their tourist visas expired, forcing them to check out of the hotel and into a flat.

Finally, 11 days after arriving in Minsk, they tried for a third time to reach Poland, travelling to Brest in the far south-west of Belarus. This time they managed to get to the Polish border, arriving just after midnight. At this point, Belarusian soldiers made a crucial intervention.

Just like Ammar, the teacher detained in Lithuania, and others who have posted on social media over the summer, the Syrians found the Belarusian military eager to assist.

As the group stood close to the border, soldiers appeared and told them to wait. Minutes later, an armoured car arrived and took them to a military truck, where Idris and his friends found 50 other migrants huddled inside.

The truck drove for a short while, said Idris. "Then the soldier asked us to wait, so they could make sure the road to the Polish border was open."

He then escorted the entire group for 200m (656ft) and, says Idris, showed them the way to Poland. Idris said the soldier even helped them cross the border.

"I believe he cut the wire for us."

Splitting up into smaller groups, and with a GPS reference to guide them to a rendezvous a few miles inside Poland, the travellers plunged into the forest.

The videos Idris sent over the next two days show the friends at their lowest ebb, the journey finally taking its toll. The distance they travelled on foot was no more than a dozen miles. But the two-day hike through swamps and dense forest brought them to the edge of exhaustion. At one point, Idris fell into a ditch and hurt his leg, losing the group precious time.

Finally, on 9 October, they reached their pick-up point near the Polish town of Milejczyce, where a car was waiting. By dawn they were in Germany, and they split up soon afterwards to go their separate ways. Jamil and Roshin to Frankfurt, Zozan to Denmark to meet her fiancé.

Idris carried on to the Netherlands, where he plans to report to the authorities. He's heard that if he is granted asylum, Dutch family reunification rules will make it possible to bring his wife and twin daughters from Kobane.

But it's going to take time.

"I've been researching refugee status in Europe," he says. "I think it will take a year or two."

It's hard to know how many people have made it to their intended destinations since Mr Lukashenko opened his country's doors.

Belarus has denied allegations of inducing migrants to fly there on the false promise of legal entry to the EU, and it blames Western politicians for the situation on the border.

At least 10,000 migrants are now in detention - in the Baltics, Poland and Germany. For many, it has been a harrowing ordeal. A costly waste of time and money - and in some cases - lives.

Across affected countries, calls for stricter controls are mounting.

Post a Comment